Active learning is broadly defined as involving students actively, rather than passively, in their own learning. Most often, this is shown in the contrast between students listening to a lecture and students working together to complete a task.

Active learning is broadly defined as involving students actively, rather than passively, in their own learning. Most often, this is shown in the contrast between students listening to a lecture and students working together to complete a task.

“You can sum up the difference between passive and active teaching methods in three simple words: ‘Ask, don’t tell’… The goal of active learning is to engage students and get them to use their higher-order cognitive skills — instead of simply memorizing definitions.”

– Scott Freeman, Biology Teaching Professor Emeritus, University of Washington

Pick one Mini Discussion below and include a 10-15 minute conversation in your next group meeting. These can help you consider philosophies and strategies for active learning that align with your teaching.

1. Try Individual Active Learning

While active learning is often associated with interactivity and classrooms with flexible seating and technology, students can still learn actively without interacting with peers or while sitting in a lecture hall. Students can work independently, actively apply new knowledge, and create evidence of their learning. These activities can be mediated by technology (or not), may take less time to execute during class than group activities, and can help encourage more independent thinking. Below are six examples of individual active learning activities. Review these and then discuss.

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Solve-a-problem

Students solve a problem individually, then compare answers with the instructor’s best answer.

Time: 2-5 minutes, plus time to explain the correct answer.

Correct the error

Students correct an error that you have intentionally made in a statement, equation, or visual. The error may be an illogical or inaccurate statement, premise, inference, prediction, or implication. Instructor concludes by soliciting examples and sharing the best correction.

Time: 1-3 minutes, plus time to explain the correct answer.

Active listening checks

Students put away their lecture notes and write down the most important one, two, or three points from the lecture, plus one question. Instructor concludes by sharing what they intended to be most important and answering questions. Optionally, the instructor can collect student responses (on paper or via Canvas, Google Form, TopHat, etc.).

Time: 3 minutes, plus optional time to answer students’ questions.

Minute papers

Give students 1 minute to respond to a short prompt, which can encourage reflection, test knowledge, elicit questions, or solicit feedback. Instructor collects responses (on paper or via Canvas, Google Form, TopHat, etc.)

Time: 1-2 minutes.

Guided notes

Provide an outline, key concepts, guiding questions, or learning objectives to guide student note-taking in class.

Time: students can complete throughout the lecture.

Graphic organizers

Ask students to diagram relationships between several key concepts from the lecture or reading. Instructor concludes by sharing their own diagram with an explanation.

Time: 5 minutes.

Discussion Questions

- Which of these example activities have you tried (or can you imagine trying) with your students? How might this individual activity benefit you and your students?

- How can an individual activity replace existing lecture material?

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Citation

Zakrajsek, T. D., & Nilson, L. B. (2023). Chapter 14: Lecturing for Student Learning. In Teaching at Its Best: A Research-Based Resource for College Instructors (pp. 261–280). John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/wisc/detail.action?docID=7191311

2. Share the "Why" of Active Learning with Students

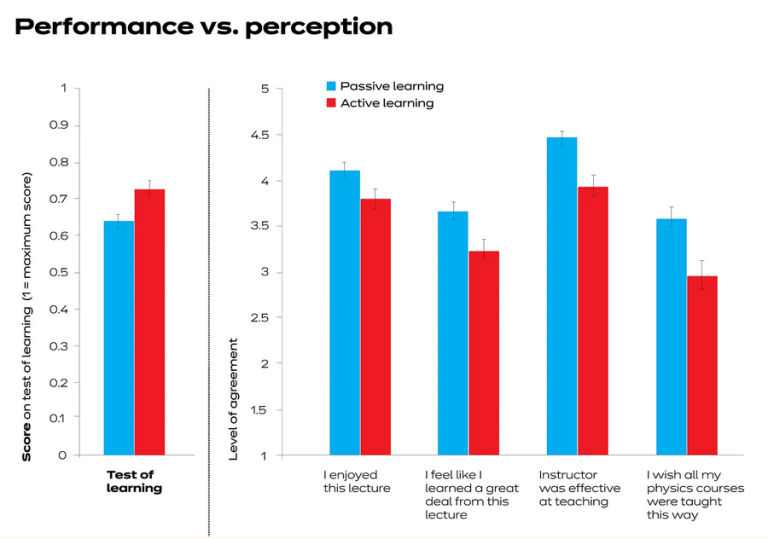

Research shows that, particularly when students are acclimated to and expecting a lecture, active learning can feel more difficult and make students feel that they are learning less. In a 2019 interview, researcher and instructor Louis Deslauriers spoke about his research into active learning with the Harvard Gazette: “‘Deep learning is hard work. The effort involved in active learning can be misinterpreted as a sign of poor learning,’ he said. ‘On the other hand, a superstar lecturer can explain things in such a way as to make students feel like they are learning more than they actually are.’” However, in tests of student knowledge retention, students who participated in active learning performed better than students in a passive lecture environment. Sharing with students the results of this study, shown in Chart 1, is one way an instructor might reveal why a class is designed with more active and interactive learning and help reduce student resistance.

Discussion Questions:

- Identify one concept or skill in your course where students could write, discuss, or practice in place of listening to a lecture about the concept or skill. How could this be more effective?

- In addition to sharing research on active learning with students, what other ways could you share with students the benefits of active learning within your class?

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Citations

Deslauriers, L., McCarty, L. S., Miller, K., Callaghan, K., & Kestin, G. (2019). Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(39), 19251–19257. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1821936116

Reuell, P. (2019, September 4). Study shows that students learn more when taking part in classrooms that employ active-learning strategies. Harvard Gazette. https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2019/09/study-shows-that-students-learn-more-when-taking-part-in-classrooms-that-employ-active-learning-strategies/

3. Adopt a Facilitator Role

When leading an active learning activity, the role of the instructor changes. If you have typically lectured, your role will pivot from being in the spotlight to being a facilitator on the sidelines. Instead of preparing talking points, you may instead provide students with clear instructions to help them arrive at their own conclusions, ask questions along the way to prompt deeper thinking, facilitate a process for students to share their thinking, and provide students with feedback.

In a spring 2019 symposium for New York University, presenters Laudien and Lopez-Fitzsimmons shared several examples of active learning activities and facilitation tips for the Humanities. One successful active learning activity described uses a picture prompt to recruit interest in Aristophane’s Lysistrata, which undergraduates may find difficult to read, interpret, and connect to their own lives. This activity helps students make predictions about the reading, helping recruit their interest and motivation. During the activity, the instructor facilitates by:

- sharing images with students related to the text,

- prompting small group discussion of the images with questions that help them make predictions about the text,

- managing the timing of the activities,

- and recording summary ideas for future discussion.

In a 2025 publication, researchers studied the effectiveness of active learning to teach DNA replication to undergraduates. They found that actively involving students in diagramming this biological process resulted in better knowledge retention by students. During the activity, the instructor facilitates by:

- leading a competitive group quiz about key concepts,

- assigning students roles within their groups,

- circulating to ask and answer questions while groups diagram the DNA replication process,

- asking groups in turn to present specific parts of the process,

- and concluding by presenting a video animation that reinforces the correct answer.

Discussion Questions:

- Consider the facilitation skills needed for the example you reviewed. What facilitation skills do you feel more and less comfortable with?

- What ideas do you have about bringing your expertise and content knowledge into a more facilitative role?

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Citations

Aguiar, A. A., & Calabrese, J. (2025). Broadening the perspective of traditional lecturing vs. Active learning in introductory college biology. Discover Education, 4(1), 278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44217-025-00729-7

Laudien, H., & López-Fitzsimmons, B. (2018, November 16). Get Out of Your Seats! Active Learning Strategies That Engage Students in the 21st-Century. Faculty Resource Network. Transforming Teaching Through Active Learning, Miami, FL. https://facultyresourcenetwork.org/symposium/november-2018/get-out-of-your-seats-active-learning-strategies-that-engage-students-in-the-21st-century/

4. Balance Student Activity with Expert Guidance

While being student-centered is an important quality of active learning, eventually providing corrective feedback and expert guidance from the instructor is still important. Undergraduate life science students who participated in a 2023 study about active learning experiences of students shared the following:

“It’s not right when everyone gets the question wrong and… [you] just say worrisome things, and groan and moan and [say] ‘Uh-oh, you all have a test on Wednesday, uh-oh.’ That’s not helping anyone. That’s not building anyone up. That’s giving everyone anxiety. That’s giving everyone a little more stress about not understanding something that we don’t even know what [the instructor is] referring to exactly. There’s so many parts of a question, we don’t even know where people could potentially be going wrong… That doesn’t give people hope or determination to figure a question out.”

“I don’t understand how you could call this a class, when they’re just throwing this stuff at you, but they’re not helping you understand it, and they’re not going back and saying, “This is wrong because of this, and this is how you do it the right way, because X, Y and Z.” I got none of that from [my instructor], and so I learned all my stuff from [a third-party tutoring service].”

Researchers found that it is especially important for students requiring accommodations that the instructor explain their expert thinking to the entire class to summarize an activity. For example, after a Top Hat question, an instructor can use student responses to target the remainder of their lecture, thoroughly explaining the process of solving a problem that many students answer incorrectly.

Discussion Questions:

- How do you use student responses (degree of success or failure with an activity) to guide your class sessions?

- Running out of time for a thorough explanation is a common occurrence in active learning classrooms. What adaptations can you make to avoid this problem?

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Citation

Pfeifer, M. A., Cordero, J. J., & Stanton, J. D. (2023). What I Wish My Instructor Knew: How Active Learning Influences the Classroom Experiences and Self-Advocacy of STEM Majors with ADHD and Specific Learning Disabilities. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 22(1), ar2. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.21-12-0329

5. Get Students Thinking and Moving

In IDEA Paper #53, Barabara J. Millis from UT-San Antonio outlines 5 active learning strategies instructors in any discipline can use. Millis calls one of these strategies a Value Line, which is designed to make students’ opinions visible as a starting point for discussions or group work. This activity also requires students to move within the classroom, which can help break up long class sessions and result in a more memorable learning experience, but also has accessibility considerations.

In this activity, an instructor presents a statement to students and provides a minute of think time for students to decide their position on a scale from 1 to 5. The instructor then asks students to line up in numerical order. While “in line” students can discuss with like-minded students. The instructor can then form heterogeneous groups of students from various points on the line for further discussion or group work. This activity can be used for content-related learning (e.g., the US should invest in more nuclear energy), or for metacognitive or process-related learning (e.g., students should not use generative AI for coursework in this class).

Discussion Questions:

- Connecting your course to real-world examples can deepen student interest. What disagreements or controversies within your academic community are relevant to your course?

- What risks and benefits do you see to students disclosing their opinions?

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Citation

Millis, B. J. (2012). Active Learning Strategies in Face-to-Face Courses. IDEA Paper #53. https://www.ideaedu.org/idea_papers/active-learning-strategies-in-face-to-face-courses/

6. Help Students Ask Better Questions

As experts in our fields, many of us are predisposed to give students information that pre-empts their questions, or position ourselves as the ones asking questions to test students’ knowledge. What if we instead helped students form better questions? Forming productive, critical questions is an essential skill in academic thinking, research, and producing new knowledge. The Question Formulation Technique (QFT) is a protocol that can guide students to collaboratively form, improve, and prioritize questions about course content, and then reflect on the process. Student questions can then be used to guide student research projects, inform Q&A sessions with guest lecturers, or structure future lectures.

In a 2024 study, the QFT was used in an undergraduate intermediate-level Zoology course (Invertebrate Zoology) to recruit student interest and structure course content. Researchers found that both the quantity and complexity of questions students generated increased through the semester, and that students enjoyed the QFT process and found the collaborative brainstorming effective. The authors note that, “Using the QFT in this course also allowed us to better understand what topics students were curious about and interested in. The questions students generated were aligned with all four course themes.” This activity used a multi-step process that included:

- Instructor presents an image of an invertebrate as a prompt.

- Students ask as many questions about the image as they can in groups, following the rules: Don’t stop to answer, judge, or discuss. Write down every question as stated. Change any statements into questions.

- Students identify questions as open or closed, and change at least one closed question to open and vice versa.

- Groups prioritize their top questions based on: interest to the team and relatedness to course themes.

- Students discuss and reflect on the process.

- Instructors categorize and evaluate student questions to guide and organize upcoming course content.

In a 2022 paper, the QFT was used in music theory courses in several ways, including to direct student homework outside of class. Students collaborated in class to form, refine, and prioritize questions about course content, and then each student chose one question to research as homework before the next class. The authors note that, “students will often come up with questions that overlap with what we instructors would ask our students. However, using student questions can result in a marked difference in student engagement and ownership of the material because the class is exploring their questions.” This activity used a multi-step process that included:

- Instructor presents a prompt: Write questions about the Bologne violin sonata movement in light of the following statement: “It is musical analysis, not musical description, that can help us understand the significance or uniqueness of a musical work.”

- Students follow rules to produce questions in groups: Ask as many questions as you can. Don’t stop to answer, judge, or discuss. Write down every question as stated. Change any statements into questions.

- Students categorize questions as open or closed, and change at least one closed question to open and vice versa.

- Each group prioritizes 3 questions, and all prioritized questions are compiled into one list for the entire class.

- Each student chooses 2-3 to research as homework and present back to the class.

- Students reflect on the QFT process: How does asking questions about music deepen your understanding or appreciation of the piece? How would asking questions about music you are performing change your learning process?

Discussion Questions:

- What benefits can you see for your students in generating their own questions about topics in your course?

- Which activities in your course could be supported by students forming their own questions?

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Citations

Burt, P., & Duker, P. (2022). Student-Driven Music Theory: How the Question Formulation Technique can Promote Agency, Engagement, and Curiosity. Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy, 36(1). https://doi.org/10.71156/2994-7073.1406

Summers, M., Fernandez, J., Handy-Hart, C.-J., Kulle, S., & Flanagan, K. (2024). Undergraduate Students Develop Questioning, Creativity, and Collaboration Skills by Using the Question Formulation Technique. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 15(2). https://doi.org/10.5206/cjsotlrcacea.2024.2.15519